Thursday, September 5, 2013 at 8:14AM

Thursday, September 5, 2013 at 8:14AM Gilad Atzmon

Gilad AtzmonA beautiful piece by Lasse Wilhelmson

http://lassewilhelmson.wordpress.com/2013/09/04/a-portrait-that-tells-many-tales/

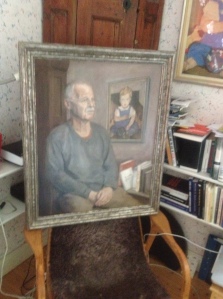

Picture: writer Lasse Wilhelmson

This is a portrait of me in my writing corner with some of the many books I have bought over the past ten years, mainly off the internet; books that are about history, but not the history told by the victors of Europe’s two world wars. A portrait of a blue-eyed, curly-haired little boy can be seen too, along with an old Swedish country sideboard.

Four Books

You can identify them in the bookcase in the picture. The Jewish Century (2004) by Juri Slezkine, a Jewish-born American professor of history with roots in Russia. It is probably one of the most important books ever written, as he himself says, if you wish to understand 20th century history. According to Slezkine, this is impossible unless you comprehend the Jewish influence. Everything from the Russian ”revolution” to European education, culture and science is dealt with in this book which also includes many statistics.

The next book is The Israel Lobby, and US Foreign Policy (2007) by two of America’s most prestigious academics, John J Mearsheimer, professor of political science and Stephen M Walt, professor of international politics. It came to be the classic that broke the official silence surrounding all discussions concerning Israeli and Jewish influence on US foreign policy.

Between these two, is my own book Is the World Upside Down? (2009). It contains a selection of my articles about the Palestinian issue, Zionism and the neocolonial wars waged in the first decades of the 21st century. They are arranged in order by time which makes it possible to follow how my earlier opinions, partly Jewish-Marxist, have changed as a result of a changing world and my in-depth studies.

The red book, The Wandering Who? (2011), is by Gilad Atzmon. He grew up in a rightwing Zionist home in Israel, where he did his military service; twenty years ago he chose exile in London where he now lives with his family. He has, perhaps like no other, deconstructed Jewish mentality which he sometimes calls Jewishness or Jewish ideology. Atzmon is also an informed philosopher and one of the world’s best jazz musicians, his favourite instrument is the saxophone.

Atzmon’s upbringing and experiences are very different from mine. I found him on the internet twelve years ago. I read one of his early articles and was astonished to find that I had a soul-mate, albeit several sizes larger than myself, apart from our ages. This was when I had just written my first long essay, perhaps my most significant, dealing among other things with Moses Hess and Karl Marx: Zionism – More thanTraditional Colonialism and Apartheid.

The Swedish marxist Jan Myrdal had always been my intellectual role-model up until then. Now Gilad Atzmon replaced him.

Boy in picture laden with symbols

The portrait of the little boy is my older brother Börje who died tragically in an accident when he was only four years old. He was the first child of the marriage between my Jewish mother and my Swedish father, a marriage that had to wait many years due to the Jewish family’s reluctance to accept marriage to a non-Jew for a daughter. Hence, in many ways Börje became a heavily laden symbol for my own family line. The portrait is painted by Jewish artist Lotte Lazerstein who fled from Germany before the onset of the Second World War. She was given refuge and assistance by my parents in our home and initially supported herself as a portrait painter.

The portrait of me and Börje also symbolises the beginning of the end of my mother’s Jewish family line in Sweden. Neither of my sisters, nor our children and grand-children are Jews. We are all secular Swedes, many traditionally confirmed in the Christian church. As the oldest child, I was the only one that worried about my Jewishness, and this led to me spending several years in Israel at the beginning of the sixties, but also to my involvement in the Palestinian question later in life. Due to my experiences, I eventually chose not to identify myself as a Jew at all. I was also liberated from a mind encumbered with Marxist thinking as the two are linked. I now had the opportunity to view religions and ideologies in a more independent and traditionally humanitarian way.

Börje has also played a very different part in my life. I inherited his portrait because I was the only sibling who knew him when he was alive, and as a child had prayed to God many times to bring him back to life. He has always had a special place in my heart, in my own life, and I have had his portrait on the wall for all my descendants to see. I have always said to them: Look at Börje, he is our Jewish inheritance, especially his eyes that are typically Semitic.

Or so I thought, until one summer I read Arthur Koestler’s book The Thirteenth Tribe. I realised that my Jewish inheritance was not Semitic, nor was its historic homeland in Palestine, but in Khazaria where the north Turkish population converted to Judaism in AD 740. At that time, Khazaria was a super power situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea along the Silk Road, and its people had clear Mongolian features. This was the summer of 2001, just before the terror attack on World Trade Center, 911.

The eyes of Börje and of the beholder

When I returned to my home in Täby from our summer house, I looked with new eyes at the portrait of Börje and suddenly saw the width between his almond-shaped eyes and the special fold of skin at his nose. What I thought I had seen all my life was not Semitic at all but Mongolian – that is to say Khazaric. And indeed my grandmother came from Grodnow, a town in what was then southern Poland, now Belarus, and had a majority population of Jews. Her ancestors had migrated from Khazaria to southern Russia and eastern Europe when the super power disintegrated sometime during the 11th century. Does anyone wonder where all Europe’s Jews came from?

Koestler’s book and how it changed my perception of Börje’s eyes was probably one of the most significant occurrences for my decision to abandon my Jewish identification – one of many I have always had throughout my life. Realising the crucial role that ”the eye of the beholder” can play for someone who believes they can see, affected me greatly.

The country sideboard

The brown sideboard seen in the background of the picture comes from my father’s Swedish family. I know little about them other than that the family was small and that my paternal grandfather worked as a farmhand in Nynäshamn and started a family in Stockholm where he worked as a turner. One day I hope to have the time to look more closely at my father’s side of the family.

Picture: The Artist Markus Andersson

Markus is one of the few well-schooled painters of oils in Sweden today, but he also paints watercolours. Like many artists from all over the world, he has visited the well-known Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum many times to learn his craft and exchange ideas. Personally, I am not a great fan of Nerdrum’s occasionally necrophobic imagery. Markus paints portraits, but also in the romantic landscape style and is deeply rooted in his Swedish heritage as told in traditional Tales of Gods and Viking legends. Markus is also inspired by Anders Zorn’s pictures of women. Many of his works have a special, warm, aching and down-to-earth tone that captures the Swedish soul. His brush also forms gossamer-light Nordic landscapes.

How we found each other

Markus and I both love the simple and earthbound life, nature, animals and wooden houses heated with logs, and carpentry. These are things that create quick friendships. And we soon realised that both of us had been appointed ideological pariahs by the Swedish so-called journalist and culture elite. Markus had been the target of a campaign that dismissed him as a dark-brown racist, almost a Nazi. Mainly because of the portrait of Christer Pettersson, but also his overall choice of subjects.

His most ”spectacular” work is a series of Swedish scapegoats, the paintings that attracted me. Especially the one of Christer Pettersson, the alleged assassin of prime minister Olof Palme who was acquitted. The painting is a masterpiece and one he has been well-paid for. Probably far too little which certainly remains to be seen.

An oil painter who paints realistic romantic landscapes and rune stones instead of modernist and abstract motifs… he must be slightly dubious? His work was dismissed as simple kitsch by Katrine Kielos in the tabloid Expressen. As far as I know the first time she has acted as an art critic. She now writes leading articles in the tabloid Aftonbladet, spreading politically correct opinions to the people. For my part, it has always been about accusations of ”antisemitism” and suchlike. But I have responded to this elsewhere.

I knew nothing of Markus’s background as ideological pariah before our paths crossed. We talked a lot when he was painting me. I did most of the talking, Markus is a quiet and unassuming person, and moreover he was busy trying to catch his model’s personal features. We spoke of art, painting, politics and ideologies, money and economy, exercise and physical training and last but not least poultry keeping.

I went to art school myself as a small child. I had forgotten all about it, but the smell of turpentine in Markus’s studio jogged my memory. My ambitious mother wanted me to become an artist or an architect. But I studied and worked with psychology and pedagogy in various environments. I never managed to explain this “occupation” to my paternal grandfather who was an illiterate pedlar.

The painting without a name

Markus usually gives his paintings names and we discussed this occasionally. Our hilarious suggestion of a title for my portrait was: ”Nazi” paints ”Antisemite”, or ”Nazi kitsch painter paints Holocaust- denying antisemite”. But that can wait. We both agreed – or perhaps quietly hoped – that this picture in the light of history, would eventually become a treasure. Although neither of us thought it likely in our lifetimes.

Chickens and ”clucking”

In the aftermath of Åsa Linderborg’s hysterical naming and shaming of me as ”Jew-hater” and ”Holocaust-denier” in Aftonbladet at the end of November 2012, I wrote a small story. Åsa’s outburst was triggered by the fact that young TV presenter of the European Song Contest, Gina Dirawi who is of Palestinian origin, had mentioned my book Is the World Upside Down? on her popular blog and suggested it was suitable ”for evening reading”.

The title of my story was ”Åsa’s clucking and Gina’s ”antisemitic” chickens”. Eventually Gina, after suffering many attacks, defended her terrible deed by saying that she had only read the first nine pages of my book. So, she hadn’t even finished the first article about my struggle with municipal red-tape in order to keep my chickens. Probably the most readable article I have ever written …

Of course Markus and Anna will buy a brood of Hedemora chickens once the chicks have grown a bit. To replace the ”multicultural” brood they have at the moment. Oddly enough, I have recently got to know two more people who keep Hedemora chickens. I like them very much too, even in other ways.

These stories were written the evening after I had fetched the painting from the glazier, framed and ready.

Täby on the 3rd of June 2013.