Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. On May 14, 1948, David Ben Gurion declared the State of Israel. By then, the Zionist forces -- vastly superior to Palestinian and Arab military capabilities -- had already expelled the Palestinian inhabitants of 220 villages and conquered about 13 percent of Palestine. This event is known as the Nakba, meaning the “Catastrophe” in Arabic.

On May 14, 1948, David Ben Gurion declared the State of Israel. By then, the Zionist forces -- vastly superior to Palestinian and Arab military capabilities -- had already expelled the Palestinian inhabitants of 220 villages and conquered about 13 percent of Palestine. This event is known as the Nakba, meaning the “Catastrophe” in Arabic.

Clik here to view.

On May 14, 1948, David Ben Gurion declared the State of Israel. By then, the Zionist forces -- vastly superior to Palestinian and Arab military capabilities -- had already expelled the Palestinian inhabitants of 220 villages and conquered about 13 percent of Palestine. This event is known as the Nakba, meaning the “Catastrophe” in Arabic.

On May 14, 1948, David Ben Gurion declared the State of Israel. By then, the Zionist forces -- vastly superior to Palestinian and Arab military capabilities -- had already expelled the Palestinian inhabitants of 220 villages and conquered about 13 percent of Palestine. This event is known as the Nakba, meaning the “Catastrophe” in Arabic.Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. By the end of the year, the Zionists’ premeditated plan to ethnically cleanse the indigenous inhabitants of Palestine would be fairly successful. Nearly a million Palestinians would become refugees, and more than 400 cities, towns, and villages were destroyed. The entire region still reels from the shock-waves of this 66-year-old calamity.

By the end of the year, the Zionists’ premeditated plan to ethnically cleanse the indigenous inhabitants of Palestine would be fairly successful. Nearly a million Palestinians would become refugees, and more than 400 cities, towns, and villages were destroyed. The entire region still reels from the shock-waves of this 66-year-old calamity.

Clik here to view.

By the end of the year, the Zionists’ premeditated plan to ethnically cleanse the indigenous inhabitants of Palestine would be fairly successful. Nearly a million Palestinians would become refugees, and more than 400 cities, towns, and villages were destroyed. The entire region still reels from the shock-waves of this 66-year-old calamity.

By the end of the year, the Zionists’ premeditated plan to ethnically cleanse the indigenous inhabitants of Palestine would be fairly successful. Nearly a million Palestinians would become refugees, and more than 400 cities, towns, and villages were destroyed. The entire region still reels from the shock-waves of this 66-year-old calamity.Below are accounts by three Palestinians who survived the Nakba, their experiences are but droplets in a sea of stories of that time. Their memories and experiences remain ever alive, and perhaps more importantly, their inner hopes and sense of defiance have not wavered, despite the passage of time and the many failures that have emerged.

The following has been edited for length and comprehension:

Khaireddine Abuljebain, 90, born in Jaffa, Palestine. Currently residing in Kuwait:

The Zionist forces, backed by the British, always threatened Jaffa. They encircled the city with colonies and set up military zones before the city fell in April 28, 1948.

On April 25, 1948, I was moving around the city after I transferred my office from the city's outskirts into its center. I was a journalist for a newspaper, a teacher and an activist, so I had a role to play during that time. The Zionist forces were shelling Jaffa with mortars. Of course, the Zionist forces had superior weaponry because the British occupation forces went after Arabs who had weapons and did not touch the Zionists. If an Arab had a rifle with three bullets, he would have been condemned.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. On that day, I was moving around the beautiful city of Jaffa, one of the economic hubs of Palestine. I note this because the youth today do not know much of the historical times of Palestine. They are always playing on the computer and know nothing of the history of Palestine, or Kuwait, or any other Arab country.

On that day, I was moving around the beautiful city of Jaffa, one of the economic hubs of Palestine. I note this because the youth today do not know much of the historical times of Palestine. They are always playing on the computer and know nothing of the history of Palestine, or Kuwait, or any other Arab country.

Clik here to view.

On that day, I was moving around the beautiful city of Jaffa, one of the economic hubs of Palestine. I note this because the youth today do not know much of the historical times of Palestine. They are always playing on the computer and know nothing of the history of Palestine, or Kuwait, or any other Arab country.

On that day, I was moving around the beautiful city of Jaffa, one of the economic hubs of Palestine. I note this because the youth today do not know much of the historical times of Palestine. They are always playing on the computer and know nothing of the history of Palestine, or Kuwait, or any other Arab country.Anyway, as I was moving around, one of the shells shot from Tel Aviv into Jaffa landed next to me and I was injured. I was lucky, they were not terrible injuries and the doctors were able to mend me quickly. They transported me home to recover with family.

By nightfall, as the whole family gathered, we had heated discussions about whether or not we wanted to stay in Jaffa. A lot of us did not want to leave, but it was a very difficult situation. The final decision was that some of us would leave. My mother, my fiance, my cousins, and I decided to leave.

On April 26, 1948, we got on a truck and headed to Egypt. My father, and other family members, decided to leave by sea because there was heavy rain and the Israelis were blocking the roads.

Why Egypt? Because it was the closest neighboring country and we already had some family there. We arrived in Gaza, desperate and afraid. Why desperate and afraid? Because there was a Zionist colony along the way that was shooting wildly at anyone fleeing.

We arrived in Gaza after a day's travel. We found thousands of refugees in Gaza, from many parts of the country, and who had escaped massive military attacks by the Zionists.

The youth should remember this, please tell them, the Zionists had a dangerous plan against us and most of the villages were wiped out and cleansed. There was a horrible massacre in Deir Yassin, which terrified everyone. Unfortunately, we, the Palestinians, were not sufficiently armed. There are many books written about the fall of Jaffa and other places. We did not have the strength to resist. Many were martyred in Jaffa.

Half of those in the truck with us stayed in Gaza, my family and I continued on to Egypt.

We got to the borders of Egypt, and luckily, we were allowed in as refugees. The Egyptians living along the border were sympathetic and very helpful. Let history record this point. They offered help and aid to us.

Along the road, we were stopped by the Egyptian police and taken to a military post in Abbassiyeh (a neighborhood in Cairo). Many of the women and children who were with us were able to escape, but me and four others – my finance and relatives – stayed there.

As a journalist, I was immediately seen by other Egyptian journalists who wanted to know what was going on in Palestine. And then the Egyptian military imprisoned me. I did not know why. I was confused and surprised. I was freed with the help of friends in Egypt.

In order to liberate the rest of my family, who were imprisoned as well, I had to sign off on paper work and pay bribes. And that is how we became refugees in Cairo.

It was soon after we heard that Jaffa had fallen to the Zionists.

Finally, I made my way to Kuwait as one of the first Palestinians teachers in the country. We were able to establish a modern education system in Kuwait, such as sciences and music, rather than language and religion studies.

Decades passed and I was elected by the Palestinians – in the first democratic elections we had – as the representative of the Palestine Liberation Organization in Kuwait.

If the right of return was implemented tomorrow, undoubtedly I would return. And if fate does not allow me to be alive, my children and grandchildren must return.

*****

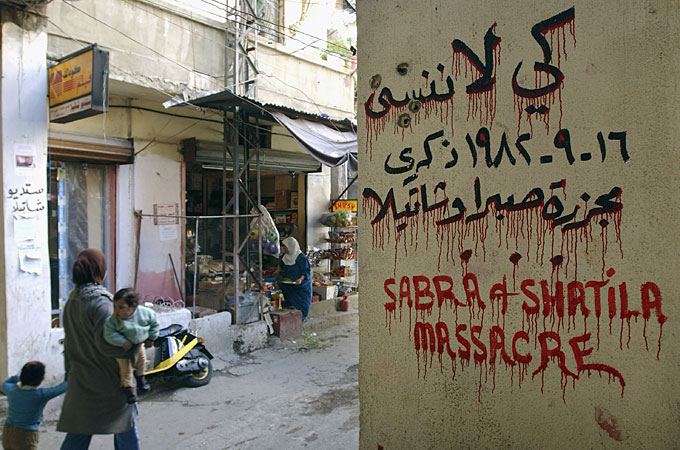

Mohammed Himmo, 89, born in Jaffa. Currently residing near Sabra camp in Beirut, Lebanon:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Let me be honest. The Arab armies called themselves the rescuers in 1948. That was a complete lie. They didn't let us do anything.

Let me be honest. The Arab armies called themselves the rescuers in 1948. That was a complete lie. They didn't let us do anything.

Clik here to view.

Let me be honest. The Arab armies called themselves the rescuers in 1948. That was a complete lie. They didn't let us do anything.

Let me be honest. The Arab armies called themselves the rescuers in 1948. That was a complete lie. They didn't let us do anything.In our area, there was an Iraqi and a Turkish commander who planned operations and we would implement them. When the Zionists attacked an area to occupy it, we begged those commanders to do something and they wouldn't move a finger.

When the resistance in our area began, we had about 700 makeshift mortars. Most of the men in my family were fighters. I remember we tried to convince these commanders to allow us to send a mortar every minute towards the Zionist positions occupying most of Jaffa. Both the Turk and Iraqi turned white and one of them said, “Do you want to destroy Jaffa?”

I replied, “Do you think anyone is left in Jaffa now? There's is no one, they all left.”

I swear, if they had allowed us to fight back things would be different. The Zionists were not ready to lose any casualties. They were not.

We were just a family, not a battalion or an armed force. It was me, my brother, my cousins – the cousins were the ones who hand-built those mortars. We moved around five mortars on simple trucks, building makeshift launchers from metal, and shooting them at places that were occupied by the Zionist forces.

But let me start from the beginning.

Life before 1948 was good, except for the British. All the problems are because of them. All the support and supplies to the Zionists were possible because of the British.

Before 1948, the relationship with the Jews was decent. There was an uprising before I could remember, but nonetheless the relationship between Arabs and Jews was alright. It was the English who really played with us all.

I remember our house was along the coast. The British police would always move around on the main street, passing by our house and headed towards Tel el-Arab [Tel Aviv]. They also had implemented a nightly curfew, and denied any large gatherings outside.

One night, I was up sitting next to the window looking out to the sea. Usually no one would be out – English or otherwise – during the night. I remember as the night went by, I suddenly saw a large number of men, more than 10, all holding machine guns, arriving on the coast. Then another group. Then another.

Another neighbor of mine, who was a fisherman and used to go swimming at night, had seen them too. It was the Jews. They were coming in force, landing along the shore.

Look, in terms of the Jews, after 1936, a boat would arrive bringing Jews from Russia, or from Germany, or from God knows where. Every week. The British would welcome them and disperse them throughout the country. They were allowed to conduct military training and they prepared themselves.

I remember, a Jewish friend of mine from Tel Aviv begged me to move to the city. This was around in 1945. He, and his brother, told me that the future was looking dark. It was as if they had already known what was going to happen.

Me and my family began our resistance operations at around 1946, getting involved in skirmishes or tit-for-tat kidnappings. The British would grab a person from the Jewish forces and gave him to the Arabs, and vice verse, just to heat up the conflict.

We really felt that we couldn't do much against the Zionists because they were backed by the British. The British had great experience bombing neighborhoods prior to 1948. Oh they bombed a lot of places.

The family and I left prior to May 1948. Most of the surrounding areas were emptied, there was no one left, and we were only 10 or 12 people. What were we going to do against an oncoming Zionist army? So we left.

We arrived in Tyre, and then we moved to Beirut. We came by road in a convoy with others. There were a lot of people in the convoy.

I remember my mother was very worried because my brother had gone the opposite direction towards Egypt. To find him, I hopped on a boat, named Serena, in Beirut and headed to Port Said, Egypt. Every person who was Egyptian was allowed to pass. Those who had Palestinian identification papers were immediately taken to prison.

The blankets were filthy with insects. We paid extra for food and for the guards to get us new clothing. But sometimes they would simply just take the money and not give us anything back. I'm still waiting, you know, more than 65 years later, for those new clothes.

I was in prison for about a month, and then [the Egyptians] took us for military training and finally to Palestine in order to fight [the Zionist forces]. At that time, I simply didn't believe they cared about us or the liberation of Palestine. [The Egyptians] treated us horribly as if we were the enemy.

I never found my brother by the way.

They took us to Gaza and there I was ordered to mainly wash dishes.

One time, by mistake, I spilled water on an officer while he was walking by. I was taken to military court for that. The judge then ruled that I was to be beaten with a rod a hundred times along the soles of my feet. I couldn't walk for two weeks after.

After a while, I decided to run away. I made my way to Nablus, passed through Jordan, and finally arrived in Lebanon.

Tomorrow, if they implement the right of return I would definitely return to Palestine. It is my country. Here in Lebanon, I am not allowed to do anything. Everything is restricted. How am I to live ?

But even if life in Lebanon is good, life in Jaffa was a thousand times better.

*****

George Agha Janian, 77, born in Haifa, Palestine. Currently residing in Brummana, Lebanon:

My father was from Jerusalem, and was part of the Armenian Orthodox sect. There is a neighborhood in Jerusalem known as the Armenian Quarter, and the family had a house there. I don't know what has happened to it now. My father worked in Haifa with customs. Haifa, after the port was established there, became one of the most important trading and business hubs in all of Palestine. He moved to that city for work, and eventually met and married my mother. My mother was from a village called Shefa-Amr.

I remember we lived on a street called Mokhalis. It was a road that kind of divided Arab and Jewish areas. In front of our house was a large piece of land, Zambar's land, and all the young boys gathered there, and then headed towards to the Dera Karmel area. Over there, next to the cinema, fights and scuffles always broke out with Jewish kids. I don't remember the reasons, really, I was just a child.

There were no major tensions with the Jews and Arabs before 1948. We didn't feel frightened by them, yet. I was at an age that couldn't completely judge the situation, but I remember how my family spoke about [the Jews] and it didn't seem like there was any hatred.

I remember my uncle used to live in the mountains nearby, and we would always visit him up there. We would always go to Jerusalem to visit my father's family too. At the time, employees of the state were allowed to use the trains without any difficulty, so we would always travel to Jerusalem.

My older brothers – both about two and three years older than me – were in a school called Deir Mokhalis in Joun, Lebanon. I left and joined them in 1948, before the Nakba happened, by taxi. At that time, I didn't feel like it was any different from the usual summer journey to Lebanon we tended to have. It was only an hour's drive.

My mother followed by boat from Haifa to Beirut. By then the roads were closed. My father joined later because he still was working in the government.

My parents left the house as it was.

After a year or two of our stay in Joun, we eventually moved to Beirut.

We all thought this would be temporary. We only realized that all hope was lost after the Arab armies went in to Palestine and were broken [by the Zionist forces].

Some of the extended family from my mother's side stayed in Palestine. Some of my father's family went to Egypt and then to Australia. Others went to Syria. Some came to Lebanon but it didn't work out and they left.

My older brother once told me that he was able to visit our old neighborhood in Haifa about ten years ago. He said that he saw old men still sitting on chairs, drinking coffee, next to our house. There was a big tree and [the old men] all sat around it, as they always do a long time ago from before 1948.

I would return to Haifa if there was one state, not Israel or Palestine, you can call it whatever you want. In fact, I had a chance to go to Jerusalem but I didn't. As long as Jerusalem is under the control of the Israelis, I do not want to go.

I have no problem with a mixed country of Jews and Arabs, Christians or Muslims. But a state that wants everyone to recognize it as a Jewish state...I do not understand this. They say they are a democratic state, they say they are modern and progressive, and they condemned the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, and yet they want to make a Jewish state. What is this?

Religion and state are different.

And is a Jew from Europe the same as a Jew from Yemen?

The right of return is important because my roots are there like the tree planted in a garden.

(Photo: Dr. Salman Abu Sitta and the Palestine Land Society)