MONDAY, MAY 19, 2014 AT 8:13AM GILAD ATZMON

Bethlehem

I arrive at Bethlehem along the same motorway as all tourists, in a taxi from the Ben Gurion airport. They arrive in coaches with their Jewish guides. Pilgrims from all over the world crowd into the Nativity Church on Manger Square. Perhaps the holiest place in the world for Christians? They buy souvenirs and go back home again as if the Palestinians do not exist. Opposite the Church, lies the prestigious Peace Centre, funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, SIDA.

The town is situated just south of Jerusalem and surrounded by The Wall and by fences. Check-points further limit people’s access and they are resigned to finding inconvenient diversions. Arbitrary travel permits for areas outside the town tear apart families that have lived in and around Bethlehem for thousands of years.

On my first evening in Bethlehem I experienced music of a rare and emotional kind. A Palestinian violinist, Lamar Elias, only 14 years old, was the main attraction and there were many children in the audience. She played sonatas by Dvorak and Vivaldi and ended up, with a trio, playing a piece typical of Arabic music, with its billowing, endless rhythmic melodies. It was quite astounding how this young woman presented and played her pieces to a large audience with such ease and grace.

On my first evening in Bethlehem I experienced music of a rare and emotional kind. A Palestinian violinist, Lamar Elias, only 14 years old, was the main attraction and there were many children in the audience. She played sonatas by Dvorak and Vivaldi and ended up, with a trio, playing a piece typical of Arabic music, with its billowing, endless rhythmic melodies. It was quite astounding how this young woman presented and played her pieces to a large audience with such ease and grace.I was reminded of my own father who, a hundred years ago, was a promising young violinist. He could not pursue a career because he had to work for a living. This was not uncommon for a working class child. He took up the violin again when he retired and played for his children and grandchildren, his favourite was Bach’s sonata for solo violin.

My thoughts went to my Swedish father and my Jewish mother, whose family I visited in Israel 53 years ago, and the kibbutz where I worked, and the Israeli family there who came to mean so much to me and my parents. There was much mutual travel between Israel and Sweden during the 1960s.

The young Palestinian violinist appears like a flower in the ruins of the Palestinian villages that I did not even know existed when I was young. I think it was these mixed feelings that brought a tear to my eye and not just the sentimentality that comes with age or that a violin sonata can set off.

Peace Centre and the second intifada

Two years after its millennium inauguration in 2000, The Peace Centre, funded by SIDA, was used by the Israeli army as a headquarters during the second intifada. The building served as protection for snipers, as a prison camp, a canteen, a rubbish dump and so on. The soldiers did not always use the existing toilets. An eye witness of the 40-day-long, violent siege and the attacks on, and damage done to the Nativity Church, described 10 years later in detail what happened in an article in the webpaper Countercurrents.

The Peace Centre’s Swedish architect, Snorre Lindquist, also mentions these occurrences in his fantastic account of the construction of the Peace Centre and how it changed his outlook on life and he became a staunch friend of the Palestinians. The Israeli army shot their way in instead of using the keys they had. How could it be that the international community, the Christian church and the Swedish government turned a blind eye and hardly reacted?

Jabal Abu Ghneim and Har Homa

From my hotel window I can see the remains of what was the townspeople of Bethlehem’s nicest and most loved place for outings. This is Jabal Abu Ghneim, a hill previously covered with woods. Now it is contained by the Wall and almost completely covered with the Jewish settlement Har Homa.

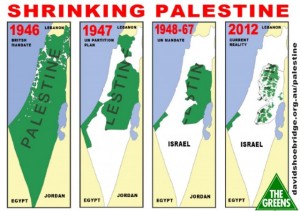

From my hotel window I can see the remains of what was the townspeople of Bethlehem’s nicest and most loved place for outings. This is Jabal Abu Ghneim, a hill previously covered with woods. Now it is contained by the Wall and almost completely covered with the Jewish settlement Har Homa.The theft of the hill and the subsequent buildings together with the theft of Rachel’s grave, were noted early on as crimes against the Oslo Agreement. Carefully chosen and with considerable symbolic value they confirmed the intentions of the Jewish state. And the whole world let it happen, just like the ongoing situation, which now points towards a final expulsion of remaining Palestinians to Jordan and a transfer of responsibility for the Gaza Strip to Egypt.

Rachel’s grave in northern Bethlehem, worshipped by Christians and Muslims alike, can no longer be reached because of the Wall. It lies quite close to the Palestinian refugee camp Aida on the other side of the Wall.

Aida Camp

Aida is a result of the ethnic cleansing 1948 – Al Nakba – and has become impoverished tenements, 4 to 5 floors high. I visit Aida a few weeks after the Israeli army’s occupation of the camp due to protests there. The Israeli writer Gideon Levi’s moving description of this in Haaretz is food for thought. I first read it when I got back to Sweden.

Aida is a result of the ethnic cleansing 1948 – Al Nakba – and has become impoverished tenements, 4 to 5 floors high. I visit Aida a few weeks after the Israeli army’s occupation of the camp due to protests there. The Israeli writer Gideon Levi’s moving description of this in Haaretz is food for thought. I first read it when I got back to Sweden.I speak to the head of the camp’s Palestinian youth organisation. We go to the place in the Wall where people blasted a symbolic hole towards the ruins of the villages from which they were expelled in 1948 when the Jewish state was unilaterally declared. He tells of tear gas, of paralysing sound bombs and of how the army went from house to house from the inside, through walls, instead of using the doors. He tells of the young Palestinian woman who died because of tear gas, the young man who broke his leg, and of all the wounds caused by rubber-coated projectiles and about the girl who refuses to go to school, traumatised by fear.

I visit the house that was most destroyed, up partly damaged stairs, and speak to a man who lives there. Many Palestinian children surround us, curious to know what’s going on. I can see a lot of mattresses hanging out to dry on the roof and there is a strong smell of urine, last night’s crop from traumatised children, many with psychiatric problems, not unusual in any refugee camp.

The young man tells how Israeli recruits walked down the alley to his house while receiving instructions from their officers as to how they should advance and aim tear-gas grenades and shoot their rubber-coated bullets. It was part of their training, as he put it. The Israeli army thus uses this impoverished refugee camp from 1948, which advocates non-violent methods, as a training camp for its recruits, in an obvious attempt to break down any moral barriers the trainees might have about attacking defenceless civilians.

The account I have of the events and how they effect the townspeople is different from that presented in the article in Haaretz. But after all, criticism of the Jewish occupation of Palestine is tolerated to a much greater extent in Israel than it is in the West, Sweden included.

The noose tightens year by year on Bethlehem and one of the holiest towns in the world is looking more and more like a prison, as are all the other Palestinian Bantustans, which together make up less than 10% of original Palestine. The Jewish state now controls life between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River. In retrospect it becomes all too clear that the Oslo Agreement was just a trick to create breathing space for more theft of land and that the so-called one state solution is a fact since the1967 war.

Deir Yassin and Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem is a museum that tells of Jewish suffering under the Holocaust. Over the years I have come to embrace a revised picture of the official one. I have not been able to find any credible evidence that gas chambers were used in Germany to kill masses of Jews and others, and that the number of Jews killed in World War II is decidedly overrated.

Yad Vashem is a museum that tells of Jewish suffering under the Holocaust. Over the years I have come to embrace a revised picture of the official one. I have not been able to find any credible evidence that gas chambers were used in Germany to kill masses of Jews and others, and that the number of Jews killed in World War II is decidedly overrated.I believe that Jewish suffering is wrongly portrayed as being exclusive compared with, for example, that of the people of Ukraine, Germany and Russia. I am also very critical of the fact that the Holocaust is used politically to motivate new wars in The Middle East. But most of all I am against the use of the Holocaust to vindicate the Jewish state’s genocide, according to the UN definition, against the Palestinians who had nothing at all to do with World War II in Europe.

For holding these and other opinions I have been subjected to a witch hunt by the Swedish media which treat the Holocaust as though it were a religion and not an event in history. In many countries in the West these my opinions would render me a prison sentence.

Is it not, however, strange that as soon as someone points out that Jewish suffering during World War II was not as substantial as claimed, all Jews protest? Should they not instead be happy about it?

Yad Vashem just happens to sit on a hill outside Jerusalem, close to Deir Yassin, further down the valley. This was the Palestinian village that came to symbolise Al Nakba – the great catastrophe – when almost 800.000 Palestinians were expelled from their homes and their villages were razed to the ground. In Deir Yassin, most people were killed, among them women, children and old people and their corpses were shown to other Palestinians in order to make them leave their homes. Most of Israel is, in fact, built on the ruins of Palestinian villages. The victims turned into executioners only a few years after the Holocaust.

The central part of the ruined village of Deir Yassin is fenced in and the site has a bar and a guard. The guard denied all knowledge of the village and barked that Deir Yassin is a public hospital for the mentally ill and that there was no access unless visiting a patient.

However, from the rear end of the area, it is possible to get a limited view. Clearly, many of the houses are built on the old stones/ruins of Deir Yassin that form the lowest level of many of the stone houses. I must confess that I found it hard to control my feelings when directly confronted with it. There were no words for the desecration in this manner of the Palestinian symbol of Al Nakba – I was quite dumbfounded. What sort of mentality would produce this absurd project?

My thoughts went to a person I know in London. He has since long worked with the organisation Deir Yassin Remembered. His name is Paul Eisen and he still identifies himself as a Jew, unlike myself. Our efforts to criticize Jewish identity have lead to us becoming personae non gratae in our countries and in the solidarity movements there that claim to promote the Palestinians’ cause. Today, these organisations are in fact controlled by Jewish Marxists and do not support exiled Palestinians’ inalienable right to return to their homes. Simply because this would threaten Jewish hegemony over Palestine.

The Old City of Jerusalem

The Damascus Gate is a powerful entrance to the market in the old city where Palestinians are still permitted to live and they dominate the area. It is Saturday and the place is full of tourists. An Israeli flag marks the house across the alleyway where Israel’s prime minister Netanyahu has bought a house incognito. One or two other houses along the Via Dolorosa, where Jesus bore the cross, have been bought by Jews. I cannot help thinking about how Jesus was sentenced to death by Romans, led by Pontius Pilate, after pressure from the Jewish rabbis – whose power Jesus challenged – and who the Romans were forced to humour in order to entrench their colonisation.

The Damascus Gate is a powerful entrance to the market in the old city where Palestinians are still permitted to live and they dominate the area. It is Saturday and the place is full of tourists. An Israeli flag marks the house across the alleyway where Israel’s prime minister Netanyahu has bought a house incognito. One or two other houses along the Via Dolorosa, where Jesus bore the cross, have been bought by Jews. I cannot help thinking about how Jesus was sentenced to death by Romans, led by Pontius Pilate, after pressure from the Jewish rabbis – whose power Jesus challenged – and who the Romans were forced to humour in order to entrench their colonisation.This Saturday, the Al Aqsa mosquewas open only to Muslims and Israeli soldiers stood on guard. Israel does”archaeological” excavations under the mosque. Will this cause it to fall down and be replaced by the Jewish Temple? If I asked this question in Sweden the media would consider it ”anti-Semitic” and it could lead to legal sanctions for ”hate speech”.

Today a group of about 30 Jewish young men in plain clothes are sauntering along the Via Dolorosa. Each one has a machine gun slung over the shoulder. They stop and block the square on Via Dolorosa. It is Shabbat and their day off. They probably come from settlements outside Jerusalem. The message to all the tourists and the Arabs is patently clear: We are in charge here and are taking over. You can see how the Palestinians feel about this by the look on their faces but the tourists do not react. I wonder what they are thinking.

Epilogue

What have I seen and learnt? Maybe more of what I already knew? But not about religions, ideologies and human rights, or colonialism and apartheid. All this gets in the way and hides the meaning and understanding of this unique project – The Jewish state – in Palestine. An ever-expanding entity on stolen ground, built after ethnic cleansing of its population. A ”cancer” in the Middle East and more.

What have I seen and learnt? Maybe more of what I already knew? But not about religions, ideologies and human rights, or colonialism and apartheid. All this gets in the way and hides the meaning and understanding of this unique project – The Jewish state – in Palestine. An ever-expanding entity on stolen ground, built after ethnic cleansing of its population. A ”cancer” in the Middle East and more.What I have described here is also an expression of Jewish mentality, seeing one’s group as chosen, above all others and realize this mentality at the expense of others – or simply Jewish ideology. It is about the meaning of the Jewish state’s Jewishness, as I understand it.

Lastly, it is significant to the answer of the question why I no longer identify myself with this state and, partly, why I have chosen to no longer be a Jew.

Relating articles:

My story of Deir Yassin, by Paul Eisen

Uprooted Palestinian

Uprooted Palestinian

The views expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Blog!